Biographical Memoir

There’s no future in the past.

My father coined this phrase. He didn’t invent it, he simply repurposed it for us. It entered the family lexicon, pulled out whenever regret crept into a conversation. His pithy take on life was very much like him: direct and to the point—For Pete’s sake, bloody well get on with it. He knew a bit about the subject.

He was born smack-bang in the middle of both rural Italy, and the Second World War. Post-war Italy faced social and economic challenge after two decades of fascism. The formation of the Italian Republic in 1946 saw the end of the monarchy, and nobility. The rate of change was great, with the gap widening between the impoverished, agrarian south and the increasingly industrialised north—a legacy of the nobility in which agricultural workers suffered oppressive conditions, and little agency, under titled landowners.

Many parts of Italy experienced grinding poverty; fortunately, my father’s family were able to be self-sufficient, and they did not go hungry. Still, the economic gloom and uncertain future forced many families, including his, to make tough decisions.

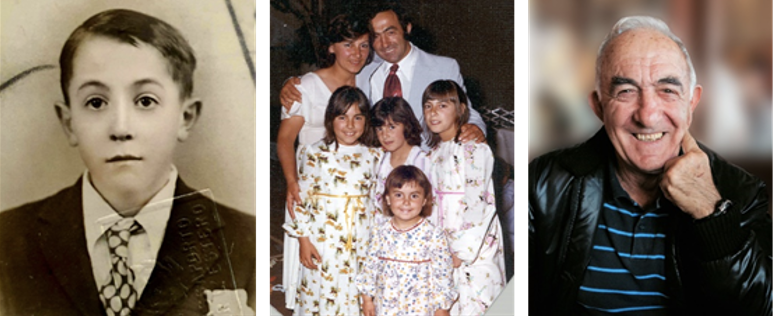

Australia pursued a ‘populate or perish’ agenda after 1945, accepting mass European immigration to help rebuild the nation. While the slogan was designed to sell sceptical Australians on the idea, Europeans—many of whom faced la fame—embraced the promise of a better life. At eleven years old, my father travelled alone from the mountains of Molise to the Western Australian wheatbelt, a journey that profoundly impacted the formation of his character, from young boy to man of courage and integrity.

*

La madre Italiana

Giovanni, torna subito a casa, altrimenti la strega ti prende.

My father grew up with the fear of the witch—la strega—drummed into him; children who dawdled home were easy prey. Post-war Italian mothers dispensed food and fear in equal measure—apron strings on constant double duty—with children inculcated into centuries-old folklore at birth. On the Epiphany eve, children were visited by La Befana, the nativity witch. Un bravo figli received sweets; un monella, a lump of coal. My father was at religious camp in an adjacent paese when he received news of his imminent departure to Australia—a gift of both sweets and coal.

Many families sent their sons at eleven because at twelve they paid full fare. My nonna was thirty-three when she sent my father to Australia. She had three sons and had lost two daughters; her husband had already been in Australia for three years. Although my father attended the village school and was a good student, education was not prioritised—an able body more use at work than school—and scant consideration, if any, was given to the disruption of his schooling. They did what they thought was best, and even though my nonna wouldn’t see her son for three years, her sorrow was tempered by the promise of prosperity. Luckily, eldest sons were crash-test dummies—pliable as putty—and he was enthralled by the prospect of adventure, mercifully unaware of its impending reality.

*

Finocchio (fennel) seeds were brought from my father’s village to Australia during the first diaspora in the 1920s. Seeds were sewn into the lining of suits to avoid customs detection.

*

Il figlio Italiano

My father’s two sisters died in infancy—one his twin—leaving him the eldest of three brothers, a fourth born in Australia. Intrigued by the otherness of his exotic childhood, my sisters and I peppered him about Italy; from an early age we were vaguely aware of our own otherness-by-proxy.

He told us how he nearly died at three and the priest gave him last rites—we weren’t quite sure what that meant, but it sounded momentous. He lived on pasta fagioli, polenta milled from corn and wild rabbit; salsiccia was made once a year when they killed the pig.

‘After daily chores and altar boy duty, I roamed the hillside in search of adventure—and castagna. It was a good, honest life,’ he said, looking wistful.

Those halcyon days ended abruptly, leaving childhood friends and younger brothers who idolised him; however, new adventures beckoned.

Italian children, coddled into middle age, were not strangers to attention; he was endlessly fussed over in anticipation of his journey. There were appointments: first suit fitting, new shoes, haircut.

He travelled to Napoli, the farthest he’d ever been. The Achille Lauro line Surriento loomed magnificently. Curious and impulsive, he let go his mother’s hand and ran the gangplank. He’d never seen a city! Never seen a ship! Scampering excitedly up each level, he grew conscious of his mother and brothers on the dock. Returning to them, he felt the ship moving. Distressed, he ran to the balcony—streamers were breaking, mother’s crying, hearts straining.

Dov’è mia madre? Where is my mother? They didn’t say goodbye. He swallowed the lump in his throat that wouldn’t dislodge for almost fifty years.

Who knew his mother’s apron strings could stretch so far?

*

Racconti di avventura

The Surriento docked in Fremantle on 10 December 1953. He never saw the chaperones paid to accompany him. Free to frolic in emergency boats strapped to the ship, had he fallen to his death nobody would have known. Once the initial shock subsided, his journey became a rollicking boys’ own adventure as he explored the ship, new friends in tow. One story achieved mythic status.

‘Dad, tell us about the matchbox and shoe!’ we pleaded, although we knew it by heart.

First impressions were important, his arrival laden with family pride. With relatives and a parish priest to impress, his appearance was choreographed: new suit pressed; new shoes, a size too big, buffed; hair Brylcreemed, combed. He had spied a matchbox on the top deck and kicked it like an Azzurri striker, sending it flying over the balcony—along with his new shoe. There was nothing to be done about it. He threw his other shoe into the ocean. What use was one shiny new shoe?

Wearing scuffed brown shoes, which had walked the land of his childhood village, he stepped off the boat; he was too excited to care how he looked. On a scorching Perth day, he went to an Italian restaurant to eat spaghetti with the parish priest, in his new suit and old shoes.

*

The foliage of Foeniculum vulgare can grow two metres high. Most Italians pick the fennel bulb before it reaches gargantuan heights and eat it fresh with olio d’oliva and sale.

*

Scuola di duro lavoro

My father was tallest in his class. He was not yet twelve years; his classmates were seven. English-as-a-second-language classes were not available to immigrant children in 1954.

A keen mind, he left school at thirteen, barely able to read or write English. While others measured trigonometry, he measured aggregate, making concrete bricks for his family’s new home. From his eight-shilling-per-week wage, ninepence was spent on comics; reading The Phantom helped improve his English.

My mother, a child of Croatian refugees, left school at fourteen. Repayments could not be made on her Malvern Star. Teachers protested, but it was not to be—Shakespeare did not pay the bills.

Achievement was never demanded of us; there was no subtle pressure to succeed or hovering over our homework. We tacitly acknowledged the arrested development writ large in our father’s determined integrity, our mother’s quiet dignity. We were leads in school plays, self-motivated to succeed—diligent, studious, achieved tertiary entry, did well, wasted nothing.

At forty-eight my father went back to school, a three-hour drive to an adult literacy teacher. His habit of dictating building quotes to my mother made retrospective sense. While I wrote essays on the significance of the rustics in The Mayor of Casterbridge, he practiced phonics.

We wore our achievements softly around his efforts.

*

Un bambino

The birth of a first grandchild is a joyous event that strengthens familial bonds. When my first niece was born, I toasted the newly minted father and nonno.

Saluti! To little miss Claire!

My father had just wet the baby’s head when the dam broke. Good whisky—twenty years’ at least—and his first grandchild did him in, finally dislodging that damn lump.

We were talking animatedly when he broke down, tears streaming his face. He spoke in gasps and fits, expunging the deep-buried trauma of being separated from his mother and brothers, and the realisation he was completely alone. He felt guilt at his mother’s distress and anger at his naïveté. I sobered quickly. It was clear I was privy to something precious, witness to an extraordinary act of unburdening. I listened closely. Dad never did this. There’s a reason I’m hearing it—I might write about it one day.

How did my father keep his trauma hidden for so many years?

*

Figlio mio!

First-born sons are revered in Italian culture. Money is offered to progeny who produce a first heir. Daughters are problematic—they have potential to become puttanas.

Mannaggia! Un’altra ragazza. Darnit! Another girl.

My father proudly produced four daughters. He lived the majority of his adult life with five females. How lucky we were.

*

Finocchio is a perennial with a short life span of three to four years. The bulb is harvested and eaten wholly, so it lives its life as an annual.

*

Mannaggia la miseria

My father was a passionate man, sometimes comically so; he once took an axe to a lawnmower that got the better of him. He could be unyielding, tough as old boots. We had a memorable stand-off; I developed a choking phobia and refused to eat stringy foods.

‘There are starving children. You’re not leaving the dinner table until you eat that cabbage!’

I felt my sisters’ woeful pity as they intermittently tiptoed past: for a glass of water, Milo, to brush teeth, say goodnight. Although he caved first—it was a school night—I wonder if he realised how much my resolve came from him.

Immigrants worked weekends to make ends meet. Wogs and dagos on overtime were ‘taking jobs from Australians’—despite said Australians not willing to forego footy and a piss-up at the club. Assimilation silenced culture, but hard work was not easily teased from the migrant psyche. It was their most valuable currency.

In his thirties, weekend work was replaced by golf, cycling, and cricket; he found balance between the ingrained Italian work-ethic and the laconic Australian approach.

I read once it takes three generations for families to exorcise the effects of war. We are three generations in. My mother tells me patience is a virtue.

*

La gioia di leggere

My parents were both voracious readers, my father’s intense curiosity finally sated. Over a good red we discussed books and life, particularly his outrage at Australia’s treatment of Indigenous people.

‘They’re second-hand citizens in their own country,’ he said. ‘Always behind the eight ball.’

One Sunday afternoon I found him with Archie Roach’s autobiography face down on his lap, his eyes closed. He had reached the part about the Stolen Generation. It was too raw. He wiped tears from his eyes, shaking his head in disbelief.

‘Those bloody bastards,’ he said. ‘No one has the right to take a child from its family.’

One of the great joys of my adult life is the time spent in discussion with my parents, particularly my father. I’m grateful for our investment in simple pursuits—enjoying coffee or wine, curing our own olives, watching Spaghetti Westerns, listening to Johnny Cash.

*

I stand in the market and hold close a bulb of fennel to inhale the aniseed smell. I am home, recalling my father’s crunch as the sweet licorice aroma lingers.

*

Morte ed eredità

‘It’ll be okay,’ he said. ‘I’m not afraid to die.’

Along with impatience, my father inherited two genetic conditions that struck at once. Unable to overcome the insidious hereditary beast, he went straight to stage four, top of the Oncology class. He agreed to treatment as a parting gift of time but had courage to call it.

He died like he lived—with strength and enormous integrity—slipping away just after Father’s Day. We slept in his hospital room that last night, like a scene from Dante’s Inferno, bodies strewn, cocooned tightly into a 4m x 6m room. We couldn’t bear to leave him. It was the six of us together, one last time.

An early memory was his mother and zia shaving his nonno’s face for burial. In peasant villages, death was part of everyday life. He had spoken tenderly of the dignified ritual, attuned to life’s precarity as a child.

As we tended him after death, caressing his waxy, paper-thin skin and combing his baby-soft hair, I was struck by his angelic likeness.

*

Buon viaggio!

This phrase always struck me as odd—travel is often bitter-sweet, tinged with the melancholia of beginnings and endings.

Two farewell journeys bookend his life; we plan his funeral like a military operation. This time, his send-off will be memorable, fitting, every nuance considered. It’s been sixty-eight years between drinks. He will not go quietly into that dark night—not on our watch.

Over time, he renounced Catholicism, unable to accept its hypocrisy—no mean feat for one indoctrinated since birth. True to his wishes, his funeral involved no religious symbolism; his cremation service included an Acknowledgement of Country. We could not have been prouder.

*

We shake the finocchio fronds until seeds fall and we store them in a warm, dry place. When the anise-like seeds are planted, a new family of fennel is born—its future is also its past.

*

La vita agrodolce

Despite its many vicissitudes, my father’s life was well lived. In death, he guides our grief: There’s no future in the past, there’s no future in the past…

He was the man we measure all others against. He often felt he fell short. He didn’t know how much he exceeded the benchmark. To endure monstrous trauma and not become a monster yourself takes courage and integrity.

He passed with high honours.

Joanne Kennedy is a published Perth writer with a Kerouac and coffee obsession. She writes poetry and memoir to forensically mine her European cultural heritage for clues to her identity. She plays Scrabble seriously and reads the dictionary for fun—and cherishes her olive-green 1960s Olivetti Lettera 32 typewriter.